EDITOR’S NOTE: Across Idaho, 11 schools are wrapping up the first year of their technology pilot programs. How are the pilots doing, and how have the schools spent their share of $3 million in state grants? For answers, Idaho Education News and Idaho On Your Side, KIVI and KNIN TV, visited three pilot schools, including Meridian’s Discovery Elementary School.

Melissa Slocum’s first-grade classroom is really several classrooms.

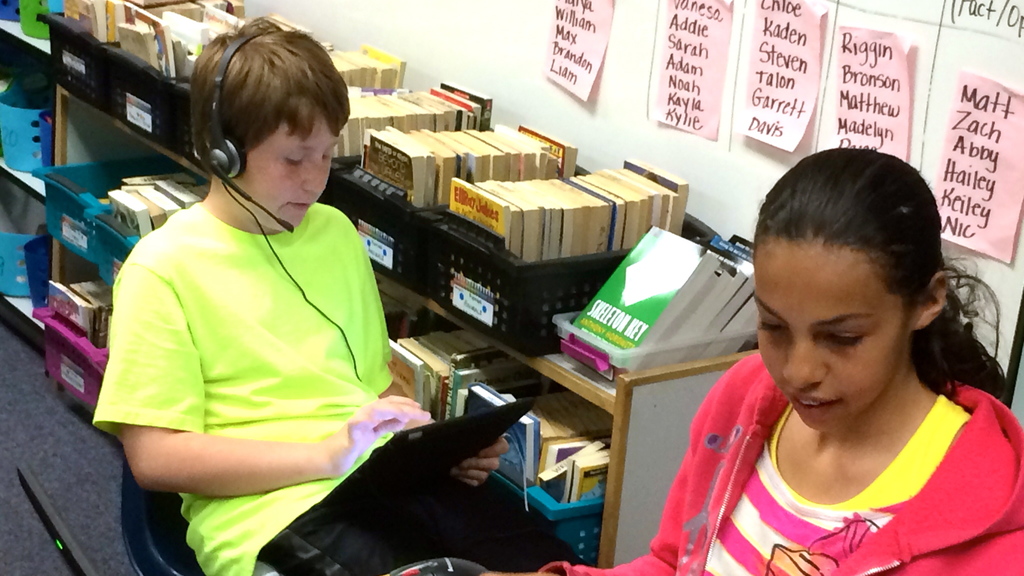

On one recent morning, two students were using iPads to record an iMovie in a “studio” in the corner of the classroom. Another group of students used iPads and Google Earth to go on a virtual tour of China and Tokyo. Other groups worked on a Promethean interactive whiteboard, an interactive table known as a slate, or on conventional laptops.

This is what Meridian’s Discovery Elementary School envisioned last year, when it applied for a share of $3 million in state technology pilot grants. Now, as the school wraps up its first year of the pilot program, the rotational learning model is fully in use. Students aren’t just on the move; teachers say they are more engaged and more collaborative, and picking up some of the skills needed to flourish under the new Idaho Core Standards.

A complicated formula

What does it take to transform a grade school into a rotational school?

Here’s the tally at Discovery, a K-5 school with an enrollment of about 530.

- iPad minis: 218.

- Netbooks laptops: 238.

- Apple TVs: 29.

- Promethean whiteboards: 22.

- Slates. 24.

- “Expressions” devices. This is the only one-to-one device Discovery uses. Every student desk is equipped with one of these devices, roughly the size and shape of an old-fashioned desk calculator. These devices allow students to take quizzes and answer questions remotely, and allows the teacher to collect student responses in real time.

While equipment accounts for the bulk of Discovery’s $370,501.35 grant, there is a staffing component: money for professional development, money to hire substitutes to cover for teachers during training sessions, and money to convert Lisa Bray’s job from full-time teaching to a hybrid role.

Bray still spends a half day teaching second grade. The rest of her day is spent as an instructional educational coach, helping her colleagues make the transition to a kind of teaching.

Empowered first-graders

For Slocum’s first graders, the transition has been seamless.

“There’s very little training,” she said, as her students moved from one 20-minute learning station to the next. “They already know how to use these devices.”

The students bring a first-grader’s sense of mischief to the classwork. The students sometimes use the Google Earth technology to locate the nearest McDonald’s, said Bray.

But having mastered the equipment — which comes almost naturally — the first-graders are also taking on other important life skills.

They are learning to work collaboratively; contrary to the perception that device-driven instruction pushes kids into a shell, the Discovery model is built around group learning. They’re picking up more problem-solving and, even in the first grade, they’re starting to develop the groundwork of the research skills that will be required under Idaho Core Standards. Slocum says technology has allowed her to gain time in her teaching day; with the rotational model, she is able to cover curriculum more efficiently.

“These first-graders have been empowered to take learning into their own hands, and they’ve accepted that.”

Changing the atmosphere

It’s too early to see if the Discovery model will result in any changes in test scores. The school, like others across Idaho, is field-testing the computer-based Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium test aligned to Idaho Core Standards.

Discovery is testing itself against other schools, however, on more qualitative measures. And some of the results are surprising.

Even though Discovery had to move quickly to launch the pilot last fall, teachers say they feel less stressed than their peers at a control school, said Bray.

And students see themselves as more collaborative than their peers at the control school.

That collaborative atmosphere, evident in Slocom’s class, is also visible in the upper grades.

It is visible in Troy Partin’s class, where students work in small groups of four to eight. The groups debate whether the sentence, “I like drawing but you might not,” qualifies as opinion. After the groups arrive at a conclusion, the group punches in a vote on one of their Expressions devices.

In Lauri Wright’s class, like in Slocom’s class, fifth-graders are embarking on a Google Earth global tour of their own. They are supposed to find an Egyptian pyramid so they can build a virtual fence around it — a test of computing a perimeter. On other stops around the globe, they are supposed to show their command of area and perimeter.

The work is done in groups — and there seems to be much more group work going on in Wright’s class than there was in the fall, when Idaho Education News first toured the school.

That’s no coincidence, she says. She has seen a lot of changes in her class. Students are picking up concepts more quickly. They are ramping up their keyboarding skills — another must under the Idaho Core Standards — as they use devices more and move from multiple-choice tests to flll-in-the-blanks tests and essay writing. They are more collaborative and more engaged in what is becoming a more active classroom.

“I’m not at the front of the room,” she said. “They’re not just sitting there alone, working on a problem.”

More reading: Here is our October story from Discovery Elementary School. And a link to Discovery’s grant application. Get more data about Discovery — a three-star school, under Idaho’s latest five-star ratings — at Idaho Ed Trends.